Virtually yours

New and old cultural institutions are building online worlds for the sharing of ideas and culture; 3D scanning is allowing established institutions to renew their online presence and new forms of digital-only museum are springing up. Most excitingly of all, 3D scanning and VR allow for ancient and modern artefacts to be experienced from the comfort of our own homes

As a result of a blizzard in Boston in January, the city’s prestigious Museum of Fine Arts elected to close its doors for the day. Realising that the decision would leave a number of eager art lovers out in the cold, the head curator of the museum’s European art division took to social media. Using the museum’s virtual reality set-up, he did a walk-through of the galleries for anyone who wanted to come along for the ride, without having to leave the warmth of their homes and hotel rooms. “There are a lot of cases like this, where virtual reality and live streaming is used to give people access to museums they ordinarily wouldn’t have,” said Brendan Ciecko, CEO and founder of Cuseum, a US company that works with museums to digitise their presence. “People can still experience the power of art no matter where they are.”

This is the new landscape of the venerable museum, where the grand galleries and sleek contemporary corridors of institutions around the world can be brought to a global audience. An art student longing to gaze at a Botticelli painting in Florence’s Uffizi can do so from anywhere. And advances in technology now allow priceless artworks to be seen in intimate detail, closer even than the naked eye, given that many renowned works are far behind velvet cords or encased within glass. And no, you don’t even need a pair of VR goggles. “Museums need to be part of the movement to have a virtual presence,” said Jill Dunne, director of marketing and communications at Cincinnati Art Museum, a 300,000 square foot institution that was founded in 1881 and houses some 67,000 pieces which date back up to 6,000 years. The majority of its paintings and artifacts - ranging from European to Asian and African to Native American - can be seen in great detail through the museum’s online presence; these include ‘Rocks at Belle-Ile, Port Domois’ by Claude Monet, or Vincent Van Gogh’s ‘Undergrowth With Two Figures’.

Much of the current focus on the virtual museum can be attributed to the Google Cultural Institute, a non-profit initiative that started in 2011. Since then, the Google Arts & Culture arm of the GCI has aligned with more than 1,000 museums around the world to digitise their collections, making them freely available to anyone at any time. Download the app and open it up to be exposed to endless options; walk through the chic galleries of the The Museum of Modern Art in New York without having to bump into anyone; zero in on priceless pieces at the Benaki Museum of Greek Civilization at the Benakis’ private mansion in Athens. “Google Arts & Culture has these partnerships across the country and has the resources to make these tremendous experiences,” said Dunne. “If people have ever said to themselves, ‘I can’t make it to the museum, but how can I get that museum experience,’ now it’s here. They can have that experience at home without going anywhere.”

|

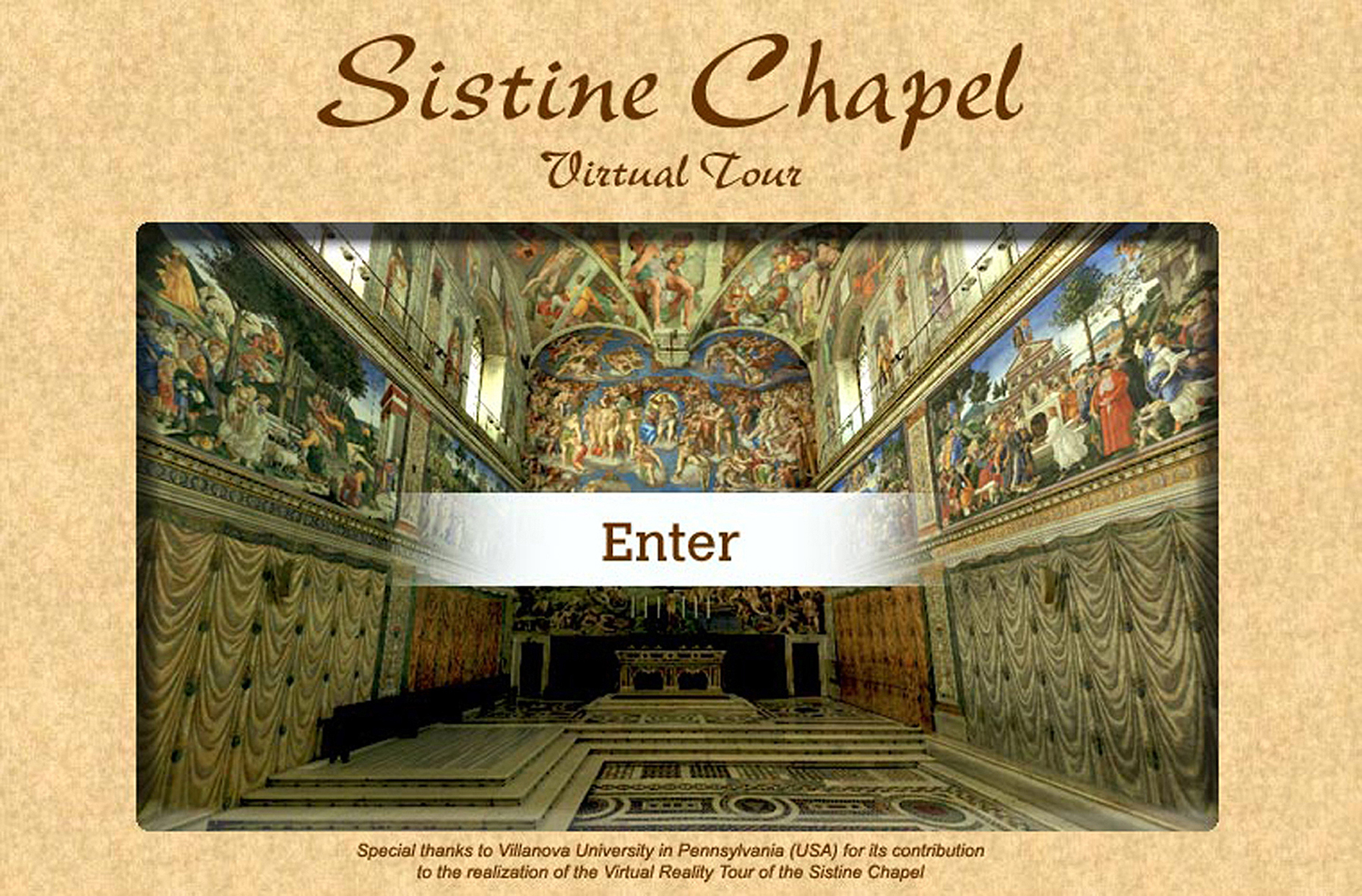

And the most prestigious establishments in the world are already very much on board; The Louvre in Paris offers a 360-degree look at its most popular exhibits, including all the background information you’d find at the site. A fan of Van Gogh? Click around the National Gallery of Art in Washington to soak in the splendor of some of the artist’s masterpieces.. Dreading the ridiculous lines to get into The Vatican? The glory of Michelangelo’s ceiling in the Sistine Chapel is just a click away. The Guggenheim, the British Museum - featuring objects from Pompeii and Herculaneum - the Dali Theatre-Museum….even NASA’s Space Centre - they are now open, free and available to anyone. Certainly, for arts buffs, it’s entertaining enough just to try out the different virtual museum modalities currently in existence. The gargantuan Smithsonian has an online Panoramic Virtual Tour that zeroes in on some of the museum’s most famous exhibits, or cast an eye on beloved pre-computer-era toys from the V&A Museum of Childhood in London’s Bethnal Green. Still, as seemingly widespread as virtual museums are becoming, is there any concern that their presence might ultimately cannibalise real-life museum visits? According to the American Alliance of Museums, the institutions contribute some US$50 billion to the US economy each year. Globally, attendance figures vary country-by-country; the iconic Louvre in Paris brought in 7.3 million visitors in 2016 - down from 8.6 million the previous year - which may well be attributable to the terrorist attacks in the city that year. Figures across the board are spotty, at best. The National Endowment for the Arts reports that attendance at museums dropped 16.8 percent throughout a period during which the US population grew by more than 33 million people and that museums started allowing people in for free. |

Conversely, Dunne says that 2017 happened to be one of the biggest years for her museum in terms of attendance. “Virtual museums are not a threat, but a complement,” she said. “Nothing can compare with actually being in a museum. But we know that people aren’t going to give up their phones anytime soon - and this way, we can be more present in people’s’ lives.” Ciecko draws a further parallel; he likens the ongoing movement to when radio and recorded music first became available to the general public. “People were fearful that everyone would stop going to concerts or seeking out live music,” he said. “But it’s the complete opposite of that. Recorded music drew more people to live events, and expanded the tastes of the public. It’s the same thing now; for a museum, it’s a hugely valuable asset to be able to deliver their collection and convey their mission through a broader set of channels.” While the end-game, said Ciecko, is for museums to deliver a “Frictionless and convenient experience” for visitors, different institutions are going about it in different ways; a number of institutions have photo-documented the interiors of all their spaces in 3D “Like someone designing a video game”, with all the attendant details and textures. |

|

There is another - and occasionally overlooked - advantage to the art of the virtual museum, and that is in the arena of performance art, a medium which can sometimes happen spontaneously. “A lot of performance art takes place at a random point in time in a museum and it’s serendipity if you happen to be there,” said Ciecko. ‘When museums started live streaming these things, rather than just 100 people being able to see it, that number suddenly leapt to 10,000.”

And ultimately, at their core, virtual museums fulfill the same cultural and social obligations that a real world museum does - to educate, inspire, inform, elevate - and to unite art-lovers in some way or another. “(Virtual museums) will have an incredibly positive effect on museum attendance numbers,” said Ciecko. “Most of the art I would go and see in person - I can see all of them online today in incredible resolution. The more people that the museum and its collections can be exposed to, the better. There’s a thirst we have for that experience.”

In tandem with the evolution of virtual museums, laser-scanning - a method by which priceless and irreplaceable pieces are replicated and thereby preserved for all eternity - has been developed. Scansite3D, a company based in San Rafael, California, has worked on projects as diverse as creating the world’s first digital dinosaur and reconstructing Tullio Lombardo’s Adam at the New York Metropolitan Museum after the sculpture fell due to a podium collapse in 2002. “Laser scanning is a wonderful way to collect extremely accurate surface information on museum pieces,” said Lisa Federici, founder and CEO of Scansite3D. “These machines act like a radar; they are non-contact and so accurate that you can often see more on the scan data than from just looking at the artifact.”Laser scanning replaces the traditional latex rubber molding procedure that museums used in the past, a system which has its drawbacks; often, said Federici, peeling off the rubber would pull away bits of the surface of the object being preserved, be it a sculpture or a dinosaur bone.

The procedure works for reasons large and small; allowing artefacts to be reproduced in VR form or even scanning sculptures for souvenir reproductions that go on sale in the museum gift shop. It’s used for insurance, for creating a copy of a work to send to another museum and for quirky things like scanning the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia, with its famous crack, so that experts can gauge how much the crack is changing year-on-year.

“It’s a godsend,” Federici said of the process. “Museums used to be very closed. Everybody kept their secrets to theselves. But I’ve seen a monumental shift around that because of all this digital technology. It leads to a whole different way of thinking.” In a data driven world where secrets are a thing of the past, these technologies are opening up a bold new future for museums and their visitors.

Others

最新动态 | 1 May 2018

The school of design that shaped the world we live in

最新动态 | 1 May 2018

Open Spaces Open Hearts

最新动态 | 1 May 2018

Homo Ex Data The natural o the artificial

最新动态 | 1 May 2018

Me2B

最新动态 | 1 May 2018

Being Human

最新动态 | 1 May 2018

Feeling AI

最新动态 | 1 May 2018

Character building

最新动态 | 1 May 2018

Tokyo 20/20