Tokyo 20/20

With the Olympic and Paralympic Games heading to Tokyo in 2020, the city is going through a flurry of urban development and design change. And the revitalisation of public space is at the heart of the project

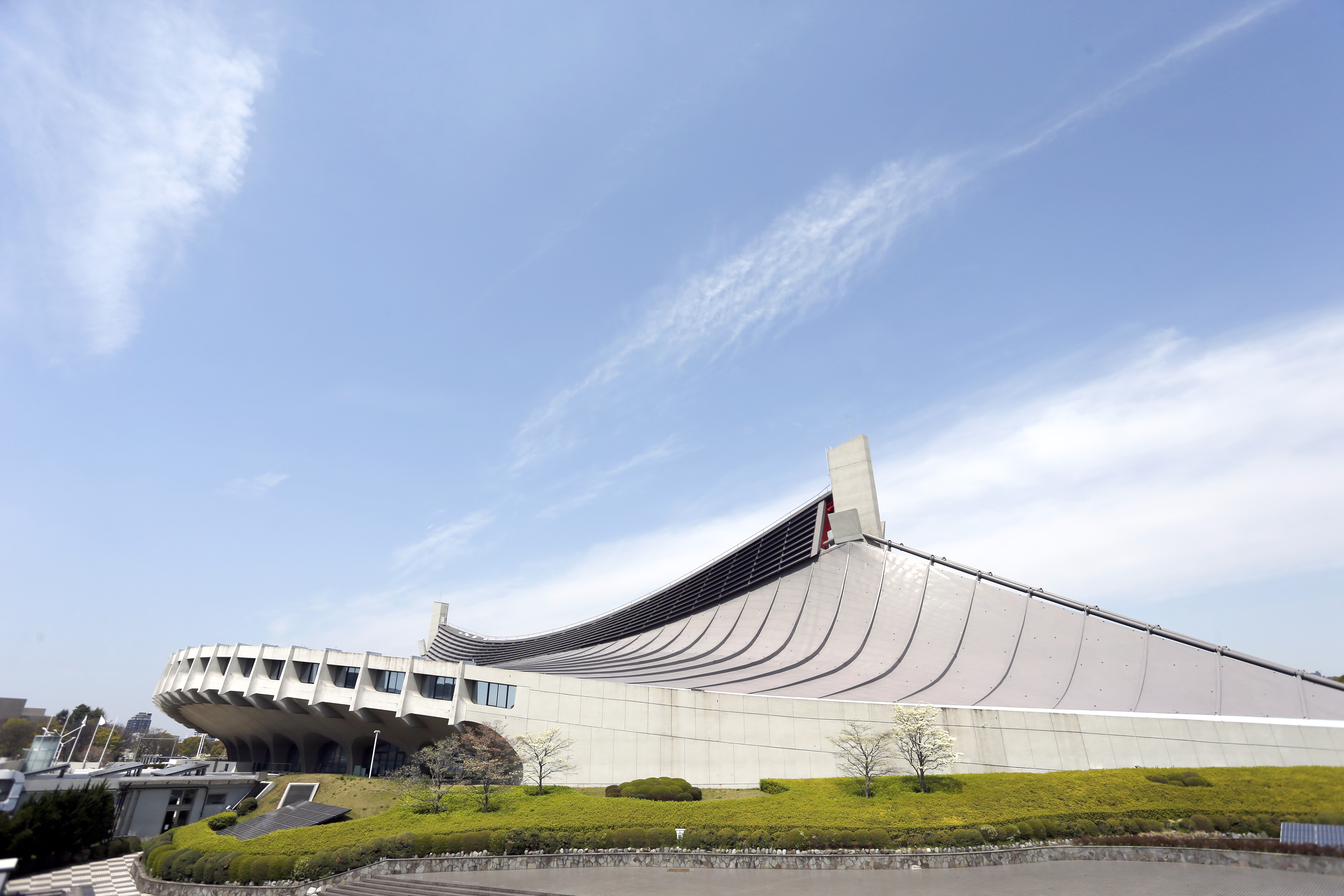

Tokyo is preparing to host the Summer Olympic and Paralympic Games for the second time since 1964 and, like most Olympic host cities, is preparing for a major transformation to accommodate the influx of travellers, athletes and visitors who are set to come through the city between now and 2020. With only a few more years to go, the city has already gone through some controversial times, whether you look to the initial National Stadium design altercation or the impending move of the Tsukiji fish market. The 2020 Olympic Games look to merge iconic venues used in the 1964 Games in an area called the ‘Heritage Zone’ and the expansion of ‘Tokyo Bay Zone’ where many new venues are being built. Regardless of all this imminent change, the slow gentrification of some of Tokyo’s most significant areas and landmarks is set to open up a broader view of Tokyo and some of the city’s lesser known areas.

Tokyo’s most prominent area of recent urban development is the expansion eastward around the Tokyo Bay Area where the Olympic Village on Harumi Island is set to be placed. As the Games draw near, the area, once a very industrial spot, will host a range of residential spaces, shops and cultural landmarks, with hopes of becoming a new central hub for Tokyo and future residents. Already, numerous new development projects have started popping up around the area and it will only get busier.

|

Another recent development in the Tokyo Bay Area is the Shin-Toyosu Brillia Running Stadium which opened in December 2016. This sleek new facility is partially run by former Japanese Olympic hurdler Dai Tamesue and boasts a 60-metre track fully covered using interiors of wood. The stadium is open for public use and the large track space, the wheelchair-accessible washrooms and change areas make the stadium a very accessible and user-friendly area unlike many other public spots around Tokyo. The new Olympic Village on Harumi Island will consist of 23 brand-new residential buildings that will be turned into rental apartments and condominiums after their Olympic use. Just as the 1964 Olympics turned Shibuya into the prominent cultural hub it is today, there is hope that the 2020 Olympic Games will bring a surge of interest to this once very industrial area. Along with plans to expand with new residences, shops and restaurants, the area is already home to a few friendly green spaces including a tree-lined bike path and Harumifuto Park which will hopefully expand over the next few years. |

Tokyo’s historic Tsukiji fish market is also set to move out to Toyosu in the Tokyo Bay Area, with a massive facility already built for the new market space. The move has been on the horizon over the past few years and the city has finally set a concrete moving date with an aim to open in October of this year. The move out to Toyosu was initially scheduled for November of 2016, but the project was subject to a lot of resentment from traders and businesses around the market who assumed the new, high-tech location could never capture the spirit of old Tsukiji. On top of that, the new outpost is located further from the city, in a less central spot. Another setback came when the groundwater beneath the new market was found to be contaminated. Since then, there’s been plenty of worry about the safety of both markets, but in the end it all boils down to food safety - and the new market is set to be equipped with industrial-grade freezers and other equipment which should ensure top food quality and safety both for traders and diners. The new Toyosu Fish Market will consist of three massive buildings which are interconnected and completely indoors — quite opposite to the original central fish market and outer market space which housed many old mom and pop shops, restaurants and landmarks like the Namiyoke Inari Shrine for over 80 years. An obvious contrast, the new space is squeaky clean and modern, with pretty much everything being visible behind glass walls including the world-famous tuna auction. Many of the best-known restaurants from Tsukiji Market will also move to Toyosu come autumn with an indoor space dedicated to shops and restaurants for tourists to enjoy and visit. The move is partially to accommodate the influx of tourists and visitors leading up to the Games while giving vendors a larger, more sanitary space, but many will maintain that the new facility doesn’t have the same charm of the old Tsukiji. |

|

|

The urban revival of Tokyo’s existing landmarks is also something the city has seen vigorously active over during the past few years with no signs of slowing down. Some of Tokyo’s most popular tourist spots are undergoing major renovations including Shibuya’s Meiji Shrine, part of the Tokyo Tower observatory and the massive expansion plans of Shibuya Station. Meiji Shrine is going through a major facelift in preparation for the shrine’s 100th anniversary which happens to fall on the same year as the Olympic Games. Visitors can still visit Yoyogi Park and parts of the shrine, but there won’t be a lot to see until 2020. Tokyo Tower is in a similar predicament, as the Tokyo landmark marks its 60th anniversary in December 2018. The tower, which is currently going through a major revamp, is looking forward to welcoming a new attraction called the ‘Top Deck Tour’ where visitors can enjoy the tower with new facilities and less wait time. |

The gentrification of Shibuya Station is one project that will not be ready in time for the 2020 Games. With an aim of completion by 2027, Shibuya, one of Tokyo’s most popular hubs for transport, fashion and culture is receiving one of the most outstanding makeovers in the city. Shibuya Station has already seen the addition of many new buildings including the design-driven Shibuya Hikarie which houses a fashionable department store, restaurants, a theatre and large conference spaces to accommodate events and other happenings. The station, which sees nearly three million people pass through every weekday, is subject to four new redevelopment projects designating four distinct areas surrounding the station itself. The new 33-storey skyscraper at the Shibuya Station South Area is already near completion and the rest of the project including the Dogenzaka and Sakuragaoka districts will follow between now and 2027. These new spots will also include a 3,000-metre rooftop observation deck towering 230 metres above the street, which is set to be completed by 2019, as well as the revitalisation of the Shibuya River space which is being transformed into a pedestrian walkway surrounded by trees and a lively plaza by this year. These new spaces will clear up the congestion around Shibuya Station; the highly anticipated observation deck will move visitors upwards where they’ll be able to get a glimpse of the city skyline and even Mount Fuji on clear days. One of the most controversial design topics surrounding the 2020 Games revolves around the new National Stadium which is set to be erected at Mejij Jingu Gaien at the southeast end of Shinjuku. The initial design by Zaha Hadid Architects was scrapped in favour of a less costly plan designed by renowned Japanese architect Kengo Kuma. Hadid’s structure caused a lot of backlash, mainly for its extravagant design and mounting costs which doubled the National Stadium budget from roughly ¥130 billion to approximately ¥252 billion. The National Stadium holds importance as it will be the venue for both the Olympic opening and closing ceremonies as well as track and field events. The old national stadium which was situated at the same site was demolished back in 2015 to make space for the new stadium which should be completed by November 2019. As part of the Olympic Game’s ‘Heritage Zone’, this stadium is set to be a pinnacle for Tokyo assimilating the legacy of the 1964 Games with the new 2020 Games. |

|

|

Many of Tokyo’s existing landmarks are also being made more accessible and public-friendly as the Olympics approach, including the Imperial Palace Garden and the Fuji International Speedway circuit near Mount Fuji which are scheduled to be venues for road cycling and race walking events come 2020. Inclusion of these famous landmarks is a spur to engage the public to take up more sporting events before and after the Games. The Imperial Palace Garden has its own charm, merging the pristine greenery and historic structures of the palace with the lofty modern buildings surrounding the area — surely one of the most unique sights in the city. On the other hand, the Fuji International Speedway, not far from the central metropolitan area, boasts the latest technology and facilities required to host world-class sporting events making it the perfect backdrop for the 2020 Games. Other than the expansion eastward towards the Tokyo Bay Area and the new National Stadium at Meiji JIngu Gaien, the 2020 Olympic Games is actually utilising existing facilities for over half the game events and venues. This resourceful use of space goes hand-in-hand with one of the Tokyo Olympics’ key goals of creating a sustainable legacy for travellers, locals and future generations that come through the city. The urban development around the Tokyo Bay Area also has high hopes when it comes to cultivating a new cultural hub within the heart of Tokyo where visitors and locals alike can both look forward to this new chapter of Tokyo leading up to the 2020 Olympic Games. |

While the Olympic Games bring forth both new design projects and the revitalisation of existing areas of Tokyo, the city continues to be at the forefront of the contemporary design industry, welcoming both leading international designers and home-grown talent from across Japan. This year welcomes back the Designart festival for its second year which is set to take place in Tokyo this October with the aim of maintaining the city’s presence as a key destination for designers. Last year’s successful event brought together works by over 200 up-and-coming designers in more than 70 unique venues, as well as designs from renowned names across the globe. The brainchild of designer Akio Aoki, artist Shun Kawakami and architects Astrid Klein and Mark Dytham, the festival is focused on the concept of ‘emotion’, and the feelings that design plays in our everyday lives. Whether it’s evoking emotion through function and beauty or new awareness brought about through movements in design and art, the Designart festival hopes to shine a light on the way design can enrich the quality of our lives, no matter where you may be living. Designart represents yet another example of the important link between the work of the designer and the emotional life of the user - a subject that is at the heart of this issue of SIGNED. |

|

Others

Latest News | 1 May 2018

The school of design that shaped the world we live in

Latest News | 1 May 2018

Virtually yours

Latest News | 1 May 2018

Open Spaces Open Hearts

Latest News | 1 May 2018

Homo Ex Data The natural o the artificial

Latest News | 1 May 2018

Me2B

Latest News | 1 May 2018

Being Human

Latest News | 1 May 2018

Feeling AI

Latest News | 1 May 2018

Character building