COMMUNITY DESIGN IN JAPAN

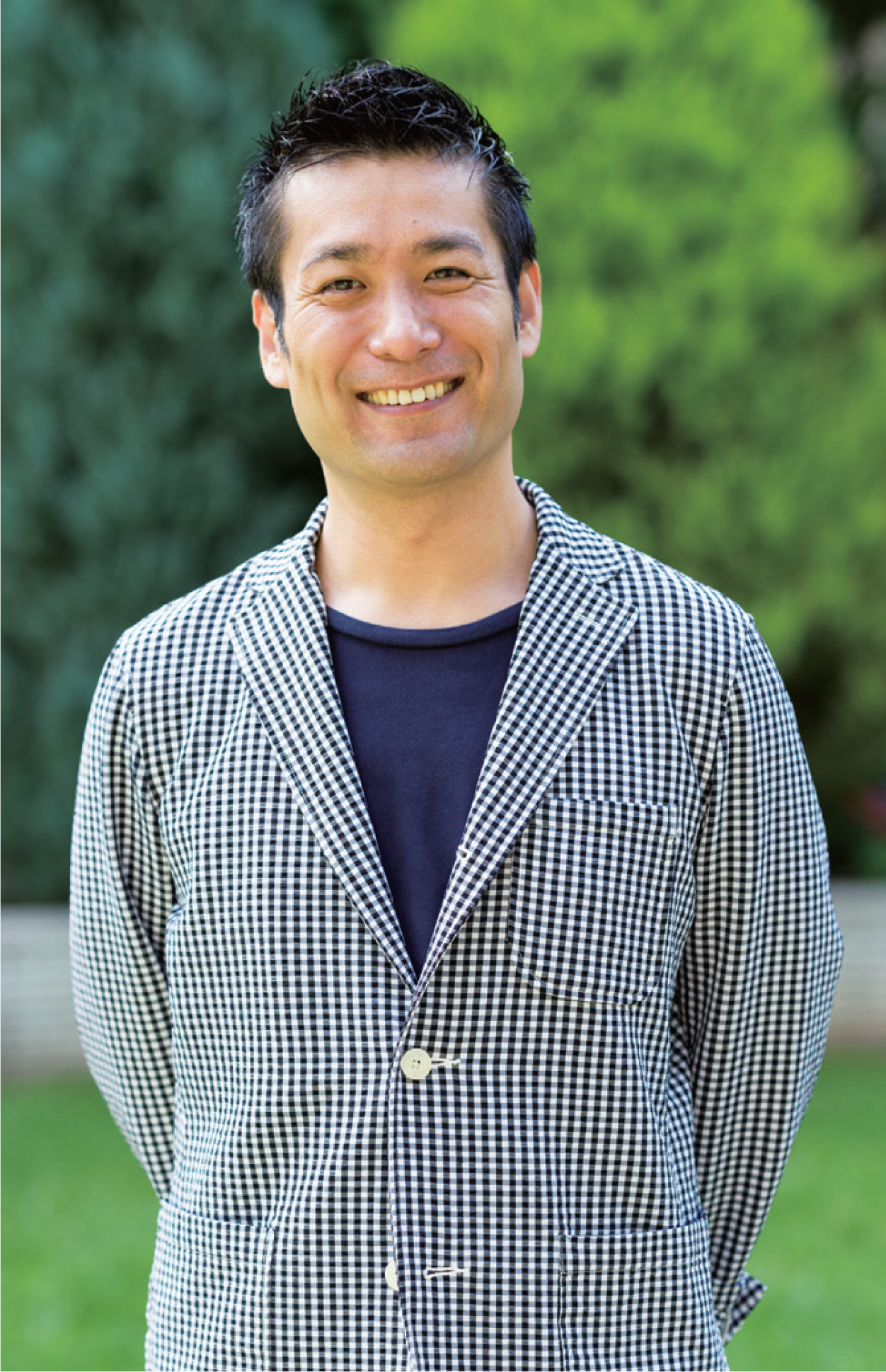

Text by Steve Jarvis Photographs by studio-L

studio-L is Breathing Life Back into Declining Communities

While Tokyo remains the vibrant economic hub of Japan, many regional cities, towns and villages are struggling to generate adequate employment opportunities and provide basic social services to their dwindling populations. Forecasts for the continued decline of rural communities are widespread, but one company, studio-L, is at the forefront of efforts to use local resources and local creativity to revitalise communities on the margins of Japan’s success story.

|

What is Community Design? Since 2005 studio-L has been helping people to come together and look afresh at the challenges they face, and the possible resources and options available to improve the health of their communities. Studio-L has pioneered the practice of Community Design in Japan. Their body of work is extensive, and includes helping bring shuttered shopping streets back to life, re-imagining dated department stores, and stimulating the creation of hundreds of small- scale local projects that bring energy and hope back to rural communities in decline. The concept of Community Design first emerged in the fields of Architecture and Urban Planning in North America during the 1960s. It was an acknowledgement that expert knowledge alone has limits, and having local input into the planning of public space produces better results for all concerned. As a design methodology, the Community Design approach starts with workshops inviting local residents to gather, discuss, and brainstorm. After consolidating these opinions, a community designer then translates them into a design project. Ideally the project will turn out to become a better utilised space appreciated by the local community. studio-L was originally conceived by its founder Ryo Yamazaki to fill the communication gap in public space creation in Japan, between local governments, architecture firms, and expected users. While excelling in this task, Yamazaki realised that community participation is most effective when participants become committed to smaller projects and activities related to the larger spaces they are planning. Whether it is a local public space or a larger community redevelopment project, studio-L’s goal is to get local participants to generate uses and activities for the project after completion of the Community Design process. Not only does this approach increase prospects for achieving social goals, it starts a ripple effect within communities. These newly strengthened bonds amongst local populations can act as a springboard for tangentially related activities to emerge, and allow for possibilities far beyond what was originally anticipated. |

The Evolution of studio-L: studio-L’s first steps into community design proved effective. Being a trained architect himself, Yamazaki was able to collate and present the opinions gathered in a way that was useful and easy to understand for the architectural firms. However, Yamazaki’s vision for studio-L went beyond just gathering opinions. He had become increasingly convinced that management of the built environment is more important than building new architecture or creating spaces. Consequently, Yamazaki resolved to use the workshops as a way to build teams of people that would then be ready and waiting to use the public spaces that were being created. In effect, he envisioned a process of creating a space with the users already in mind. Japan’s prolonged economic recession, rural depopulation and demographic decline loomed ominously, and the consequent falling usage of public space since the 2000s has translated into reduced government spending on public spaces. With fewer opportunities to plan new parks and community centres through participatory design workshops available, Yamazaki started thinking of ways to manage space with civic participation. He was now on the path to being a community designer. “If no new public facilities are going to be built, then there is no point in trying to bring people together to discuss what kind of spaces they would like to have built. Instead, I thought why don’t we bring people together to discuss how they can solve or improve the issues facing their communities.” A critical step for Yamazaki, “It was the beginning of a new era for me and for Community Design. We asked local residents to come together so we could collectively discuss the issues facing their community and come up with activities that could help solve these issues. We then formed teams of participants to sustain the ideas that they had put into place, so that they could begin to solve their local issues gradually over time. In other words, in the age of population decline, I thought that what was needed was a kind of Community Design that doesn’t make spaces.” |

|

|

Yamazaki illustrates the importance of this shift with the example of government-generated Development Master Plans. “One of the more conventional approaches to revitalising an area is for the governments, in collaboration with consultants and business groups, to create comprehensive 10-year plans. However, the local people directly affected by the plan will know nothing of the comprehensive plan, most often not even aware of its existence. What studio-L can do is a similar comprehensive plan with local people collating, synthesizing and distilling local opinions and wishes through the workshop process. Additionally, we also incorporate actual activities local communities desire into the comprehensive plan. Essentially it is the same approach as the public space design, but can be used at a wider scale, and can be tailored to help communities that are struggling with particular problems.” Another less obvious advantage of the studio-L approach happens between the participants. “Holding workshops helps people become familiar with each other, strengthens bonds, creates friendships, and on occasions can even play cupid. These are human connections that go beyond the simple building of public space, so the workshops take on a greater meaning within the community,” says Yamazaki. This wider perspective catches the essence of the studio-L approach to community building, and is a foundation for the increased vibrancy and potential that is captured in the Japanese word machizukuri. It is a concept that goes beyond simple town planning, or creating a space, activity, or business. Machizukuri is more about the re-enlivening and creating of social connections between people, which in turn becomes the raw material for building stronger and more vibrant communities. Although offers of work flow in from private industry to, for example, increase social interaction in a new apartment building, studio-L tends to work primarily with local governments that actively seek community participation in projects. For Yamazaki, it is a highly meaningful focus for the company. “Working with bureaucracies is not easy, often a slow problematic area to work in, but because the challenges local governments are dealing with are often very serious and complex in nature, these are the type of problems that can also benefit most from the reframing and creativity that can be initiated through the Community Design process.” While defying easy definition, Yamazaki is happy to call his work Community Design. “Community Design is a technique that helps members of a community to revive their own local community through the power of design. It is akin to community organising and community empowerment, but what sets our approach apart from these other strategies is the central role that design plays. Local residents are not motivated just by rational organisation. Positive effects are what draw people’s interest and make a project sustainable. In other words, it’s not just about being 'correct.' You also need people to feel that something is fun, beautiful, delicious, comfortable, or cute in order for the project to succeed. This is why we refer to what we do as 'design,' rather than 'organisation' or 'empowerment.' ”

|

In its 15 years of operation, studio-L has worked in a diverse range of settings, from revitalising marginalised small villages and towns to fortifying inner city areas. The solutions they work toward are equally diverse, and include re-branding existing community spaces and businesses, assisting in creating completely new businesses, and instigating social enterprises and volunteer-led activities. There is no set target for these solutions, sometimes increasing tourism may be a focus; other times diversifying the varieties of use of a location is a good option; or, they may be focusing their attention on developing human resources in particular areas that can then take the lead in developing their communities. While it is difficult to distil the studio-L approach into a formula, there are four important elements they usually adopt. The first step is an “Interview” process. They go into an area and talk to 3 people about the particular issues they are dealing with; on completion they ask them to introduce a further 3 more people they can interview. This process of talking and requesting contacts continues until they have interviewed about 100 people in the area. After talking to 100 people it is possible to get a profile of the community: who is respected, who works well with whom, and who has interpersonal conflicts. After gaining this knowledage they are ready to proceed. The next stage is to open “Workshops.” As they have done extensive interviews and created personal relations with the people they have interviewed, it becomes easier to invite them to workshops and solicit involvement. The workshops involve brainstorming and team building, but workshop facilitators aren’t just trying to get ideas out of people, they are building the groundwork for actually putting these ideas into action. This leads to the next stage “Team Building” as workshops start to focus on connecting people and creating teams that come up with concrete plans. Lastly, the “Action” stage, where studio-L supports community action, helps get access to funding and make appropriate connections to smooth the process. While the above four elements cover the basic flow of a project, more than anything, the studio-L approach to Community Design puts the local people at the centre of any activity. Local people know better than anyone what needs to be done, and what resources and options are available. Moreover, studio-L does not enter into any project with preconceived answers or strong feelings about what must be done, rather their job is to listen, distil and guide where appropriate. Their work is guided by the firm belief that it is necessary to trust what the people come up with as being the correct course of action.

|

|

|

Hajimari Art Centre—An art gallery for all Hajimari Art Centre is founded on the principle of “anyone can be an artist” and is dedicated to exhibiting Art Brut, also known as Raw Art, a genre where art is created by people without formal art education. It is a genre of art that finds a place for all, regardless of whether they are a grandmother, or prisoner, or have some form of disability. This sense of openness extends to the surrounding community, which was involved in the creation of the centre using studio-L’s Community Design methodology. A series of workshops helped refine the goals and activities of Hajimari (a word meaning “to start”) into four areas: food, attractive expression, children, and the making of things. Heading toward the centre opening in 2014, teams worked together to create related activities in areas as diverse as cooking, gardening and artwork creation. These four core areas continue to be explored through the lens of open- ended creative expression, with regular exhibitions, workshops and local events. With its café and multi-purpose spaces continuing to attract locals, it has succeeded in bridging art expression and community engagement in a way that has made it a leading space for unconstrained creativity deep into the surrounding regions of northern Japan.

|

Kokorozashi Shien Project— Creating a wave of local events Rural Hiroshima, like many regional areas in Japan, suffers from long- term declining population and related challenges with employment and service provision. The Kokorozashi Shien Project was the centrepiece of the 2017 Satoyama Future Expo, a year- long project organised by the Hiroshima Prefectural Government to reinvigorate local towns and villages by attracting people to visit the rural areas and rediscover the attraction of country life. The prefectural government engaged studio-L to run its Community Design programme in each rural district, with the goal of maximising visitor numbers by holding as many small-to-medium scale local events and ongoing activities as possible. The Satoyama (a Japanese word for the shared space between the human world and nature) Future Expo wanted to expand the interpersonal relationships, both within rural communities and over the rural-urban divide. In this spirit, studio-L’s programme guided participants through the four-stages of project creation and team building, with an emphasis on projects that would attract people from outside to visit their communities. In addition, the large scale of the project, and the availability of sub- project support funding, necessitated an additional tutorial class on funding application, as well as tutorials on marketing their projects to potential participants. Nearly 1000 people attended the studio-L programmes, giving rise to over 150 separate events over a 9-month period that attracted more than 100,000 participants. Events offered were as diverse as learning to fly drones in rice fields and conducting local history tours. While the figures alone are impressive, it is the interpersonal connections and new bonds of trust forged as community members worked together that were considered the most significant result of the entire project. For communities so often battling negative impressions of rural life, proving to themselves the efficacy of branching out into new areas, and with new collaborators, has set a foundation for positive future developments.

|

|

Others

最新動態 | 1 December 2019

The Future is Human-Centred Design

最新動態 | 1 December 2019

HKDI x Art in MTR — “TKL_WE_IMAGINED” Exhibition

最新動態 | 1 December 2019

Students from HKDI and MMU Joined the Global Design Camp

最新動態 | 1 December 2019

DESIGN STUDENTS’ JOURNEY TO THE WORLD

最新動態 | 1 December 2019

CREATING CITIZEN DESIGNERS

最新動態 | 1 December 2019

CITY REPAIR — DESIGNING NEIGHBOURLY RELATIONS

最新動態 | 1 December 2019

SOCIAL DESIGN X TECHNOLOGY — THE WAAG SOCIAL TECHNOLOGY ECOSYSTEM

最新動態 | 1 December 2019

SOCIAL DESIGN — CREATING POSITIVE RELATIONSHIPS

最新動態 | 1 December 2019

HOW DOES DESIGN INFLUENCE THE MODERN WORLD?

最新動態 | 1 December 2019

Interview: Paul Chapman : Virtual Reality as a Tool to Integrate Sciences, Arts, and Technology

最新動態 | 1 December 2019

Interview : Hernan Diaz Alonso : Embracing Multiplicity and Disorder in Today’s Architecture and design