Value-based Design as a path to Action

|

Text by Steve Jarvis (Photo by GoodGym) Modern life is burdened with so many problems that even when a project succeeds, it can leave one with a sense of rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic. However, there is cause for optimism. As the preceding stories make clear, things get better when people get connected. Professor Kees Dorst helps us to understand this process and its importance. |

|

Value As a bookend for this three-part investigation into Human-centred Design we talk to Professor Kees Dorst on the subject of designers anchoring their work at the value level, and the key role this form of ‘deep design’ can play in transforming societies. A leading figure in Design theory and its practical application, Dorst’s Frame Innovation methodology offers one promising approach to dealing with the many complex and difficult to solve problems found in modern societies. At its core, Frame Innovation is a problem framingmethodology. Dorst elaborates, “It is not about changing people’s opinions about something, but more about bringing people to a level of common understanding of the deep issues, and helping them to imagine different ways of thinking about the problems being faced.” The critical steps in re-imaging social problems are exploring the values of those connected to the problem. “To get a good grasp at what are the core problems and core values involved we first need a rich understanding of the situation. People have to step away from their roles and preconceived ideas to get closer to the root causes of the problem, rather than just dealing with abstractions and the simplifications that hold the problem in place.” For Kees, “the big question is not what action, but what values are we trying to achieve.” At every stage of design in the stories featured we see clear examples of these processes in action. In the first issue, Signed #22, the central role of studio-L, City Repair, and Waag is to provide a framework to bring groups of people together to communicate what is important to them, and to help them build understanding and agreement on what actions should be taken. Further, all three of these stories identify project ownership as central to their work, spurring those directly affected by a problem to dictate the parameters |

|

Action (Photo by Street Debater) The stories featured in these threeissues are proving effective because they identify and creatively address the root causes of the problems they face. Whether it is a solo design effort, such as Eatwell, or community design efforts as with studio-L, listening, accepting, and putting people’s primary concerns at the centre of all action is the common trait uniting the stories. This process of identifying what is important is the central building block for Dorst’s Frame |

|

Significance (Photo by Empathy Toy) Frame Innovation is like taking a holiday from understanding how we think a problem works, and it holds the possibility for such creative abstractions to generate fresh approaches to serious problems ailing society. But what can it tell us about driving deeper and more widespread social change? In his own work with the Designing Out Crime Research Centre, based in Sydney, Australia, Dorst has seen

|

|

Message (Photo by Empathy Toy) When asked about the future of social design and how designers can adapt, Dorst responds: “For effective social design, designers need to understand what is the social space, the space where you find and build on things in common. Even when people come from very different perspectives they may still have the

|

Others

Latest News | 1 December 2020

Music Therapy Tea House

Latest News | 1 December 2020

Human Light

Latest News | 1 December 2020

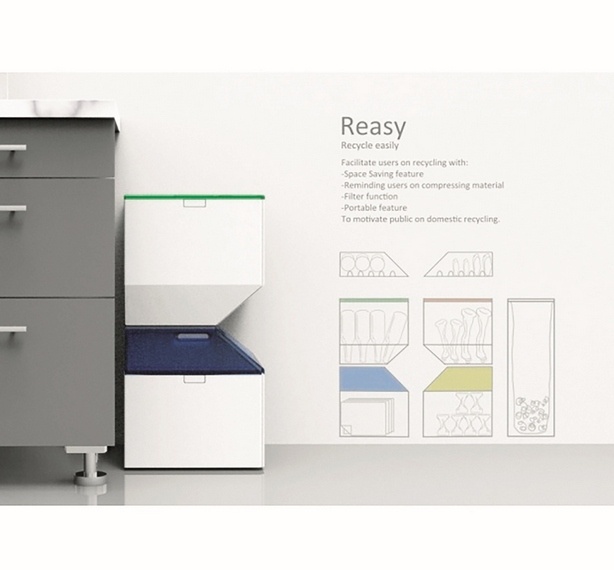

Reasy

Latest News | 1 December 2020

Design Thinking PMQ

Latest News | 1 December 2020

New Generation, New Force

Latest News | 1 December 2020

Designing for basic Human Needs

Latest News | 1 December 2020

Sharing about Death Gives Meaning to Life

Latest News | 1 December 2020

Functional Fashion is a Bridge to Society

Latest News | 1 December 2020

Tableware Designed with Love

Latest News | 1 December 2020

A Toy for the Twenty-first Century

Latest News | 1 December 2020

Design by People for People

Latest News | 1 December 2020

Stories to Drive Change

Latest News | 1 December 2020

Miffy

Latest News | 1 December 2020

Latest News | 1 December 2020